Are Fees Eating Your Returns? What Every Investor Should Know About Mutual Fund Costs

- bryanjepson

- Aug 6, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Oct 14, 2025

As a financial planner, I review a lot of investment portfolios and have learned a few things by doing so. There are some common mistakes eating into portfolio returns that investors are unaware of or have just overlooked. Over my next few posts, I am going to discuss some ways that we can all be a little more careful with our portfolio selections. Today’s post is about paying attention to hidden fees, namely mutual fund expense ratios and sales loads.

First, why do I refer to them as hidden? They are not actually hidden. They are published in the prospectus that every investor gets (and none of us read) when choosing a new fund. They are also available on most investment sites like Yahoo Finance (which is my favorite site for reviewing fund/stock performance and details: www.finance.yahoo.com). You can easily look them up.

However, they are often hidden from your consciousness because the funds don’t report to you how much is coming out of your accounts every year. Expense ratios are reflected in a lower yearly performance and sales loads lower the amount that gets invested. If instead you had to write a check each year to the mutual fund company to cover their fees, you would definitely be more aware of them.

But you should pay attention to them! Here is why:

From The Physician’s Path to True Wealth by Bryan Jepson MD

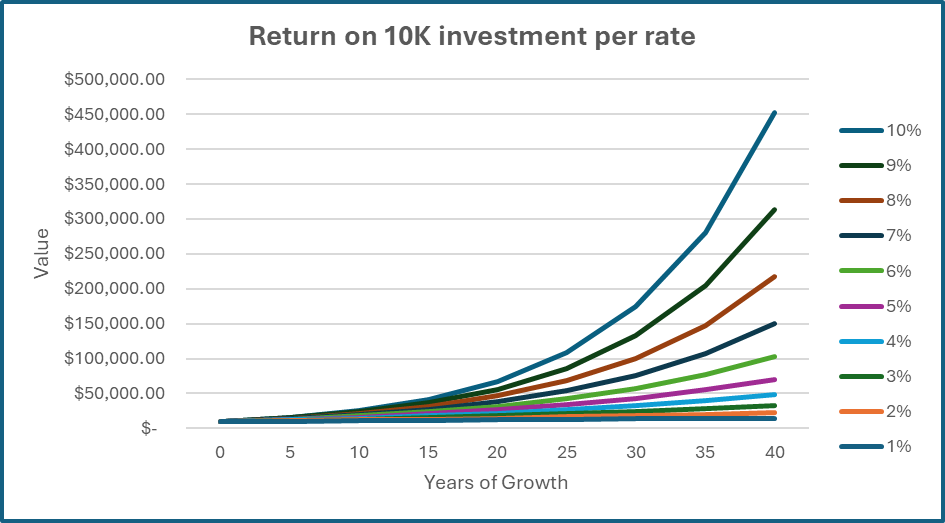

This is a chart from my book showing how an initial investment of $10,000 grows over time at different rates of return. You can see how the curves at the higher interest rates are obviously exponential, and the result may be a difference of six-figures over time. And that is just with a $10,000 investment. If you have a million dollars invested, the impact is significantly higher. So, anything that is eating into your return is preventing compounding growth on that amount.

What are expense ratios? An expense ratio is the standard administrative fee that is charged each year by the mutual fund company to pay the manager and cover the other costs of running the fund. In an actively managed fund, the manager makes a lot of decisions about buying and selling and spends time researching what companies are appropriate for the fund to invest in—all in an effort to outperform the market segment that they are targeting. (Spoiler alert: they rarely succeed!) The more specialized the market segment, the higher the expense ratio. For example, a small cap or emerging market mutual fund manager makes more money because it requires more research to find good companies.

The typical range for actively managed mutual fund expense ratios is 0.5% to over 2%. This is automatically paid out of your investment growth every year, regardless of how the fund performs. If you use a financial advisor that charges you an AUM (Assets Under Management) fee, you are familiar with how it all works. Think of the expense ratio as the AUM fee that you are paying to each manager of every mutual fund that you are invested in. And if your personal AUM advisor is charging you 1% and putting you in mutual funds with expense ratios of 1% or higher, you are losing more than 2% of your growth every year. Refer back to the chart above and look at the difference in outcome with a 2% change in return. It’s a big hit!

If you do choose to invest in actively managed mutual funds because you assume that the money manager is a professional and is therefore likely to make you more money, you should check that assumption at the door. 80-90% of mutual funds underperform the market indexes of the asset classes that they are targeting over the long term when you factor in their fees. They might have a couple of good years and attract a lot of customers but rarely sustain it for more than a few years at best. So, you need to ask the question: are they worth it, or am I just paying someone more and earning less? Compare the funds 5- and 10-year returns to the relative index fund and see if they are outperforming by enough to justify their fees. If not, it’s time to get out! (And I would suggest that you never get back in.)

Is there an alternative besides picking your own stocks (individual stocks don’t have expense ratios)? The answer is yes. There is a very good alternative with lower costs and better long-term performance: index funds.

Index funds are mutual funds designed to simply match the market segment that they are targeting, be it large cap stocks, small cap stocks, international stocks or even the total US stock market. They have a manager but he or she doesn’t have to do much work because they don’t really make decisions about buying and selling. They are just tracking the index and being sure that all the companies are represented. This is referred to as passive management, and the cost is low. The expense ratios for passively managed index funds typically range from 0.02% to 0.20% depending on the index they are tracking. That’s a huge difference compared with actively managed funds and means more money stays in your account to compound over time.

The other great thing about index funds is that they never underperform the segment of the market that they are targeting because they are designed to match it. So, although you won’t beat the market, you will outperform all but about 10-20% of active funds over time. Paying less. Outperforming. It’s a no-brainer choice in most situations. (ETFs are also passively managed funds with low expense ratios like index funds but trade more like stocks).

What about sales loads? Many actively managed mutual funds charge additional fees to participate that comes out whenever you buy or sale shares. These are called sales loads, and they come in different shapes:

1. Front-end load: This is charged at the time of purchase. A percentage of your investment is deducted up-front, reducing the amount that actually gets invested. So, if you invest $10,000 in a fund with a 5% front-end load, $500 is taken out as a sales charge and only $9500 is invested. This is common in Class A shares.

2. Back-end load: This is charged when you sell your shares. The fee usually declines over time and may disappear entirely after 5 to 7 years. It is designed to encourage investors to stay invested in the fund and not move their money out too early. You may pay 5% if you sell in year 1, 4% in year 2, and so on. It is common in Class B shares.

3. Level load: This is an ongoing annual fee on top of the expense ratio. You pay a consistent annual charge (often around 1%) for as long as you hold the fund. There is usually no front-end or back-end load, but the ongoing fees add up. This is common in Class C shares.

4. No load: These are funds that do not charge any front-end or back-end sales loads. They still may charge other fees (including expense ratios) but no direct sales charges.

If the expense ratios are for administrative costs and to pay the fund manager, then who gets the sales load? Well, the answer is in the name. It is a SALES load. The vast majority is paid to the broker that sold it to you, as a commission, with a small portion retained by the mutual fund company for administrative expenses.

Why is it important to know if your broker or “advisor” is recommending a fund to you with a sales load? Because if they are, they are earning a commission on that recommendation! That is selling, not advising, and is dripping with conflict of interest. Given everything that I have just said about administrative costs eating into your investment dollar’s future return and the success rate of most actively managed funds, it is very likely that this is not the best fund for you to be invested in anyway. So, buyer beware!

If all I said about fees eating into returns is so important, then doesn’t that apply to financial advisor fees? It is a common and reasonable question. The answer depends on what other value your advisor is providing for you and if that matches or exceeds their cost. If, as an advisor, I help you review your portfolio, uncover the hidden fees, and get you into lower cost index funds, just that often more than pays for my fee. The value of an advisor should go well beyond investment returns if they are providing comprehensive financial planning and helping you avoid costly mistakes. If they are only managing investments for you—especially if putting you in high-cost funds—and not providing the other services, then I would find it hard to justify their fee. Here are a couple of previous posts that talk more about that: My Journey from DIY Investor to CFP® — and How to Choose a Financial Advisor, Fiduciary vs Suitability: How to know if your advisor puts you first.

If you are interested in becoming a client and letting me review your portfolio, create a comprehensive plan and show you how a quality advisor can help you financially, connect with me here for an initial consultation: https://calendly.com/bryan_jepson/30min

Disclaimer: the material in this blog post is intended for general educational purposes only and should not be considered specific financial advice. You should always consult with your personal financial advisor to see how it might fit within your personalized financial plan.

Comments